By Mildred Searcey

Pioneer Trails, Vol 6 No. 3 Spring 1982

Published by the Umatilla County Historical Society

Permission to use this story granted by the Umatilla County Historical Society, Inc. Back issues of Pioneer Trails are available for purchase from the historical society.

Onthe agriculture scene pea production is a fairly new crop in Eastern Oregon, and one that has had an interesting history during its development.

In 1928 Frank Sloan, who worked for the Washington‑Idaho Seed Company, came into the Athena area, and talked some of the farmers in the foothills into planting dry peas for seed.

Four years later Sloan encouraged Barney Foster to raise a few green peas to see if the land and weather conditions were agreeable for a pea crop. When the peas were nearly ready for harvest, W.S. Miller, Lowden Jones and P.J. Burke of the Walla Walla Canning Company came out to the Foster ranch where they inspected the field. Mrs. A.J. Wernsing, daughter of Mr. Foster, remembers that when the peas were ready for harvest, she, along with several other young people went to the field on top of the hill and in the early morning hand‑picked the peas and put then in sacks.

The peas were then taken to the Walla Walla Cannery where they were hand shelled and processed, the results later determining the success of Mr. Foster’s venture. The rest of the crop was left in the field to dry to become seed peas for the next year.

The peas that were canned made 80 cases, and these cases were broken up and sent to various agriculture brokers throughout the United States. The reaction was enthusiastic about the grade and tenderness of the Eastern Oregon vegetable.

In 1933, Harold Barnett planted 40 acres of green peas and used the first viners. Here again Frank Sloan was instrumental in helping out in this venture. He suggested that P.J. Burke, through his connections at the Walla Walla Cannery, secure some vincrs from a machinery company in Wisconsin.

These viners were a far cry from present equipment. There were 8 viners, and they came by railroad car and had to be put on carts to be transported to the Barnett and Foster ranches. Don Weber of Athena remembers that Mr. Foster had two horses, Pat and Milt, which they hitched up to the hay mowing machine to cut the peas in windrows. Don and Barney Foster took turns driving the team, neither very sure of what they were doing. Trucks were then brought into the fields where the peas were hand pitched on the trucks, hauled to the viners and hand pitched off the trucks into the viners and then hauled to the cannery.

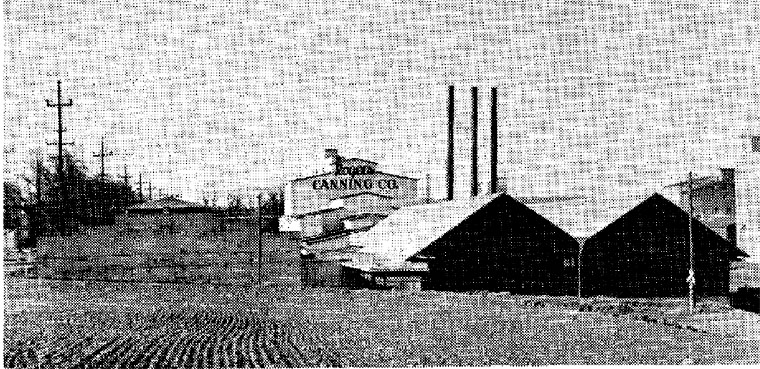

P.J. Burke, with more courage than money and impressed by the results of the Barnett and Foster venture, promoted a cannery at Athena with the following men as directors: Harold Barnett, P.J. Burke, E.C. Rogers, Barney Foster and L.L. Rogers. The date was January 12, 1935, and the name of the cannery was the P.J. Burke Canning Company.

A perishable vegetable, the pea must be harvested at the peak of perfection to produce any profit for the farmer. Before the farmer plants the pea crop, the canneries in the area must know how many peas they need for processing the next year. Based on this information, men from the canneries contract the number of acres a farmer can produce, the type of peas, the date of the planting and the price based on the grade of the pea. The contract is also based on the capacity of the cannery per day.

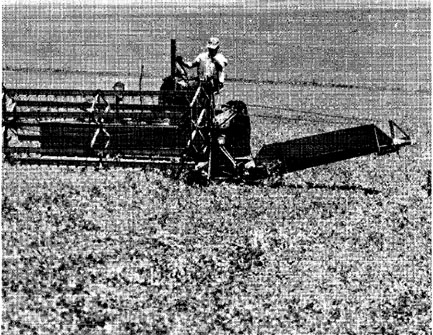

After the peas are planted and have matured and are ready for harvest, the swathers move into the fields cutting windrows. In some fields the loader then goes down the windrows, loading the vines into trucks which haul the peas to the viner station where the peas are hulled and then trucked to the cannery.

In other fields, a combine picks up the windrows made by the swathers, vines the peas which are then trucked to the processing plant. This is a faster and newer method of harvesting.

There is an old cliche “alike as two peas in a pod,” and with this thought in mind it is interesting to note how one farmers’ crop is kept separate from another’s.

At the processing plant the farmers have dumping stations. When a given number of pounds have been dumped into a container, the container auto‑matically empties and the amount is registered on an overhead dial. In addition, a tenderometer grades the peas for tenderness which determines the quality of the pea crop.

Peas are planted in the lower elevations and then staggered by calendar weeks on up the foothills. In some places the elevation can vary as rruch as 3,000 feet. Cared for by Mother Nature, the green pea has put many a furrow in a farmer’s brow. If the weather turns hot suddenly, if a warm wind continues for a twenty‑four hour period, or there is too much rain, the calendar planting is thrown out of balance.

Pea harvest is a day and night operation, and many young people in the area have acquired college educations by working in the harvest, either in the field, driving the trucks or working in the canneries or processing plants.

During World War 11, German prisoners of war were used to help the labor shortage. They were housed at the former C.C.C. Camp at Squaw Creek. Also during this time and following the war, the labor problem was relieved by Mexican Nationals who were given work permits to enter the United States. These workers were contracted for by the Pea Growers Association, and in addition to equitable wages, they were provided food and housing with shower and laundry facilities. Most of the Mexicans knew very little English, and most Americans knew little Spanish, which made pay day most interesting.

When the workers arrived in the Athena area, they were issued a button with a number on it. This number was recorded opposite the worker’s name on the payroll books. On pay day the workers would line up outside the back door of the bank and were allowed to enter in groups of. five at a time. An interpreter was present who explained to the Mexicans bow to endorse their checks. The interpreter also explained to the bank employees what to do with the Mexican’s money. Ninety‑nine percent sent their checks home. The bank employees then made out a Bank Money Order instead of a cashier’s check because the Mexican banks honored a money order more readily because it had the word bank printed on it. Cashier’s checks were often questioned. The money was usually sent to wives, mothers or sisters. One transaction required three bank employees and the interpreter for each Mexican worker, who then left the bank by the front door. All transactions were recorded, which is a customary procedure of banks, but proved a wise move in handling the Mexican payroll checks.

More than once the bank was contacted by the Mexican government asking if a Mexican worker had sent money home to his family. The Mexican postal department often pilfered the mail, and the bank’s verification of the transaction was the only record of the Mexican National providing for his family. At a time when there was an acute labor shortage, the Mexican worker was life blood to the pea indvistry. The worker is available, dependable, and the present pea farmer owes much to this program.

An interesting side light on one of the workers concerns a young Mexican laborer who came from a remote part of Mexico where bicycles were the only mode of transportation. Each year that the young man came to the United States, he spent all his spare time around bicycle shops, haunting repair and parts departments and learning about the maintenance of a two-wheeler.

Near the end of the period when the farmers no longer contracted for the Mexican labor, the young Mexican lad stopped coming to work in the pea harvest. Upon inquiry it was learned that he had saved enough money to set up a bicycle repair shop in his own community and by Mexican standard. was considered a well‑to‑do man.

Another interesting fact is that the swathers and loaders used in pea harvest were developed by J.E. Love of Garfield, Washington from innovations suggested by men from the Pacific Northwest.